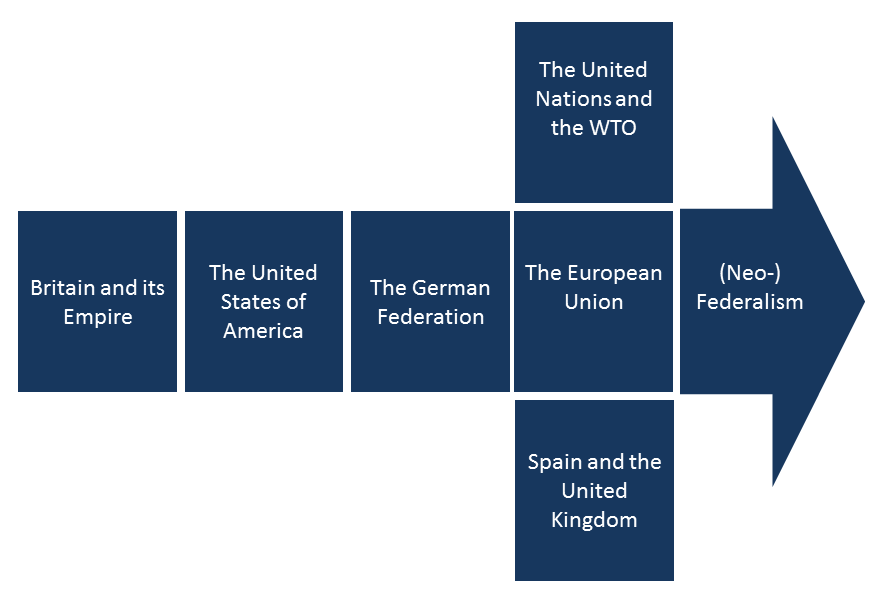

Subproject 1: International “Federalism” – Britain and its Empire

Subproject 2: Mixed Federalism – The United States of America

Subproject 3: National Federalism – The German Federation

Subproject 4: International Federalism – The United Nations and the WTO

Subproject 5: Supranational Federalism – The European Union (and NAFTA)

Subproject 6: Regional Federalism – Spain and the United Kingdom

Subproject 1: International “Federalism” – Britain and its Empire

Modern federalism emerges with the rise of the Westphalian State system. The peace of Westphalia introduced a distinction that would structure our modern legal imagination: the distinction between national and international law. The former was the sphere of subordination and compulsory law; the latter constituted the sphere of coordination and voluntary contract. Federal relations are seen as voluntary contractual relations under international law between sovereign states. We can see this “international” understanding of federalism in the eighteenth century constitutional history of Great Britain. The first episode of the modern federalism debate is the debate on what kind of union should be established between England and Scotland (“incorporating union” versus a “federal union”), and the discourse on the constitutional philosophy of the British Empire. Both British legal discourses betray the international format of the federal principle as a principle governing the relations between sovereign states. This sub-project looks at both legal discourses.

Subproject 2: Mixed Federalism – The United States of America

The international format of the federal idea prevailed at the time of the American Revolution. And it is only against the intellectual background of eighteenth-century federal thought that we can appreciate the semantic revolution that was to take place in America. The ‘Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union’—the first American Constitution—had still breathed the classic tradition of the federal principle. The semantic departure from the classic tradition came only with the second American Union. The meaning of the federal principle would be forever changed by the most important ‘speech act’ in the history of constitutional federalism: the 1787 Constitution of the United States of America. This subproject builds on some of my previous work on (early) American federalism. It looks at the Madisonian understanding of the federal idea, and in particular at the constitutional debates over the nature of federalism in nineteen-century America. What is striking about the nineteenth century American discourse is – except for the period surrounding the Civil War (1861-65) – the absence of the abstract idea of sovereignty.

Subproject 3: National Federalism – The German Federation

Victim of the nineteenth century’s obsession with sovereign States, German federal thought came to reject the idea of a divided or dual sovereignty. Sovereignty was indivisible, and the ‘new’ federalism was thus thought of in terms of a sovereign State. The ‘Federal State’ was seen as the ‘new world’ that de Tocqueville had been searching for. This subproject looks in detail at the genesis and evolution of the idea of the “Federal State” in the German constitutional context. It begins with an analysis of the 1871 Imperial Constitution, moves to the 1919 Weimar Constitution, and finally looks at the federal philosophy behind the 1949 Bonn Constitution. Each constitution will be explored alongside three dimensions. First, what were or are the political and constitutional safeguards of federalism in the three constitutional periods of German federalism? Where or are there constitutional conflicts in which distinct visions of sovereignty come to the fore? What is the role of the “regional” States? What is striking about the German conception of federalism in the twentieth century in is its success in other European States – for example France.

Having shown the historical flexibility in the meanings of the federal principle, the Second Part of the project wishes to use the federal principle for an analysis of three contemporary legal developments with regard to vertical power sharing between people(s). In contrast to the diachronic approach of the First Part, the Second Part will thus have a thematic approach. It looks at contemporary expressions of the federal principle on three levels: the international level, the supranational level, and the regional level. Each level corresponds to one sub-project.

Subproject 4: International Federalism – The United Nations and the WTO

In the twentieth century, the philosophy behind classic international law became increasingly unable to provide an undistorted reflection of the changed social reality of international relations. The shockwaves of the Second World War blew away the blind belief in an international legal order founded on the idea of State sovereignty. The rise of international cooperation caused a fundamental transformation in the substance and structure of international law. The transition from a law of ‘coexistence’ to a law of ‘cooperation’ changed the structure of international law ‘from an essentially negative code of rules of abstention to positive rules of cooperation’. The – solidified – expression of this new philosophy of cooperation was the spread of international organizations. The United Nations (1945) and the Word Trade Organization (originally: GATT, 1948) represent that spirit most clearly. And at the beginning of the twenty-first century, both international organisations have become so important that they influence many “domestic” questions within States. May we normatively qualify this development with the language of federalism? This question occupies the fourth sub-project.

Subproject 5: Supranational Federalism – The European Union (and …)

How will the European Union fit into federal categories? Here, de Tocqueville’s quest for a new word for an organism that lay between international and national law was answered by a neologism: supranationalism. Europe is still celebrated as sui generis. But the sui generis ‘theory’ has always been but a veneer. For in times of constitutional conflict, Europe’s old sovereignty tradition returns and imposes its two polarized ideal-types: Europe is either an international organization or a Federal State. And since it is not the latter, it must be the former. Yet more recently, European constitutionalism has come to accept the idea of divided or shared sovereignty – even if in the indirect form of the theory of “constitutional pluralism”. This subproject looks at the conceptual potential of analysing the European Union in federal terms, and thereby builds on previous work of mine. Yet it also involves important new aspects, such as the emergence of “fiscal federalism” in the Union after the sovereign debt crisis.

Subproject 6: Regional Federalism – Spain and the United Kingdom

The last three decades have seen the rise of a new regionalism within States. The two paradigmatic examples here are Spain and the United Kingdom. (However, in the last decade the devolution discussion has also intensified in Italy.) The rise of a “meso government” (M. Keating) is fascinating as it represents a constitutional expression of the principle of subsidiarity and its preference for smaller political units over bigger ones in the exercise of public functions. The Spanish decentralisation process started thirty years ago (1978-1983) with the emergence of Autonomy Statutes and Autonomy Agreements. A similar process of devolution has more recently taken place in the United Kingdom. At the end of the 1990s, British devolution saw the establishment of regional assemblies in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. National constitutionalism thereby still strictly distinguishes “devolution” from “federalism” by pointing to the sovereignty of the nation state. But is this not a legal veneer over a different political reality? The family resemblance between regionalism and federalism will be discussed in this sub-section.